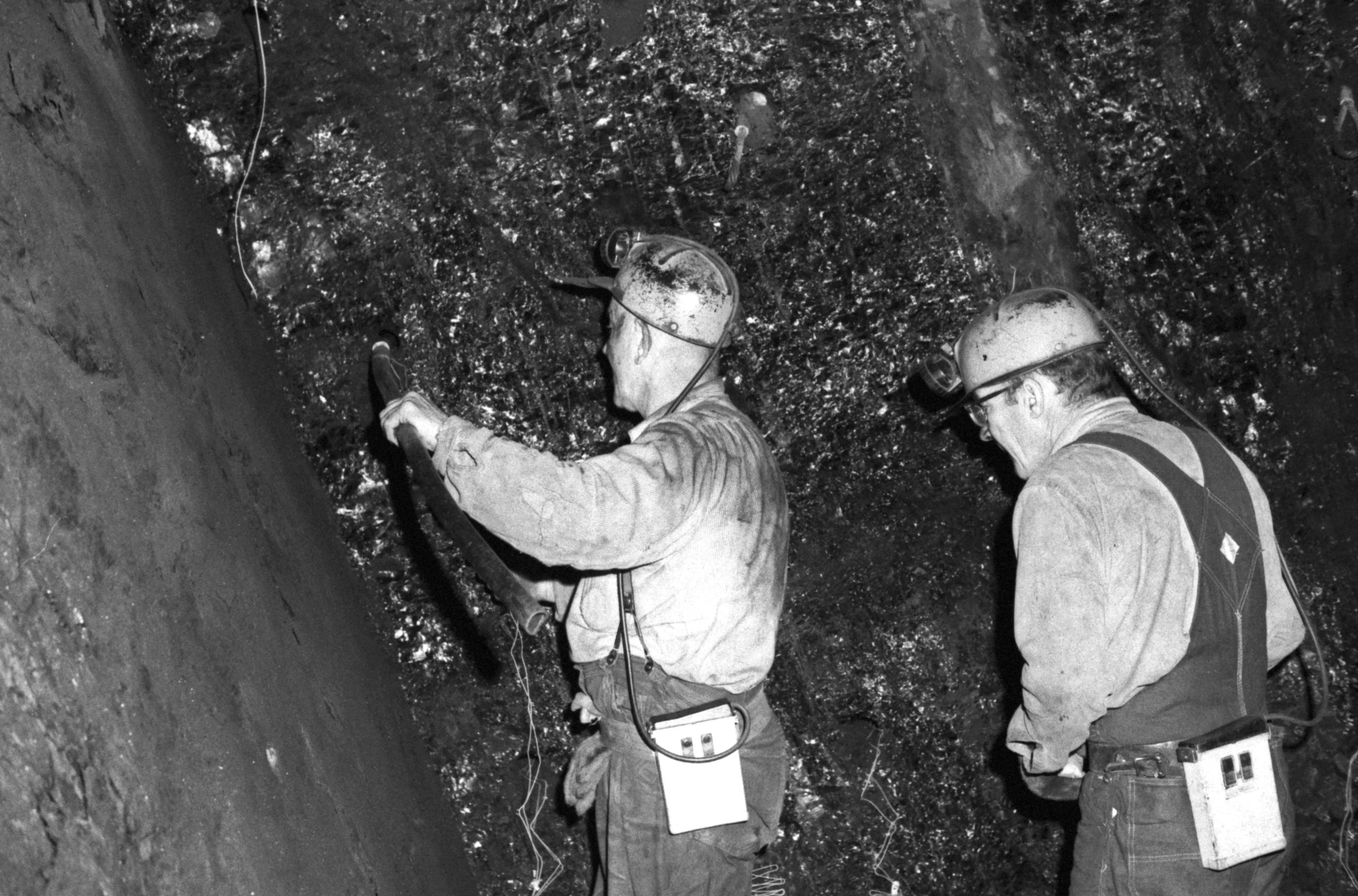

In this photo from April 1974, John Streepy (left) and Bill McLoughry (right) stand before the working face of the Rogers No. 3 coal mine preparing to load dynamite. Streepy is using a black plastic pipe to push sticks of dynamite into 2” diameter holes drilled 8-feet into the working face. About 16 holes perforated the face of coal to insure a successful shot. The drilled holes were spaced, and the dynamite charges timed to break but not pulverize the coal. Following the dynamite blast, the coal was removed and the working face of the mine advanced after building a roof from timber props and thick boards, called lagging.

Rogers No. 3 in Ravensdale was the last underground coal mine in the state of Washington. Streepy and McLoughry were seasoned veterans who worked around coal mines most of their lives. This photo comes courtesy of Barry Kombol, who worked in the mine and on several occasions stayed the second shift documenting the daily labors undertaken by his fellow coal miners.

The Rogers seam was first opened in 1958 from a portal on a hillside above the Summit-Landsburg Road that later became known as Rogers #1. A second portal adjacent to the Summit-Landsburg Road opened the following year and was called Rogers #2. The third and final opening, Rogers #3 was 500-feet north of Kent-Kangley Road near 262nd Ave. S.E. The combined mines operated on four different levels, reached underground depths of 800 feet, and produced over 493,000 tons of coal during 17 years of operation.

To the left is a stratum of bedrock called the footwall by miners. To the right and out of the photo was the hanging wall. Just above McLoughry’s head was a small vein called parting rock, comprised of carbonaceous shale. The Rogers seam was 16-feet wide and stood nearly vertical, unlike most coal mines that operate on horizontal planes, as sedimentary formations are naturally deposits. The forces of plate tectonics uplifted the Cascade Mountains and altered the local Ravensdale geology to this rare condition – a seam of coal tilted to more than 80-degrees.