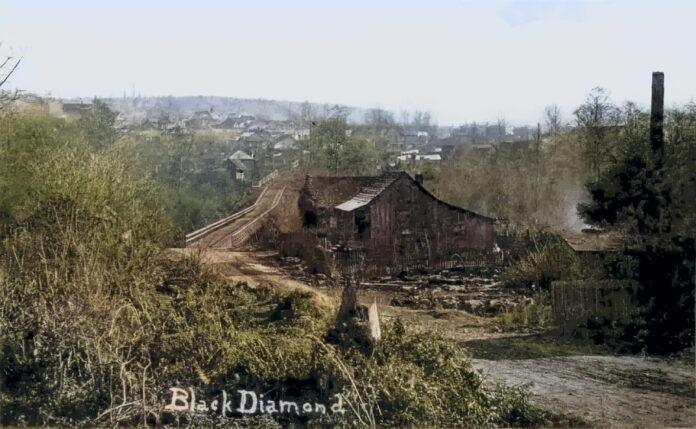

On Morgan Street in Black Diamond, about halfway between the cemetery and Old Town, this long bridge once spanned a small stream called Ginder Creek. The old bridge which probably spanned a distance of 200 feet was torn down in the 1920s. This road was originally known as the Cemetery Hill Road #128, and later called S.E. 325th Street. It probably gained the Morgan Street name after the City’s 1959 incorporation.

Today a 5-foot diameter concrete culvert, likely installed in the 1950s allows Ginder Creek to flow beneath the road that connects Morganville to the historic commercial center where the Museum and Bakery occupy buildings constructed when coal was king and Black Diamond was among the largest towns of King County.

Why this long bridge and not a simple culvert? The answer lies in modern earth-moving machinery. In the 1800s, moving dirt was labor-intensive and expensive. To fill a valley from both sides required large numbers of men loading dirt onto horse-pulled wagons, then hauling and dumping it in place. With an abundance of local timber, it often made more sense to just construct a wooden bridge on short piling. However, the introduction of the steam shovel, early combustion-engine tractors, and later diesel-driven bulldozers changed all that. Moving dirt became far cheaper than building bridges, plus their subsequent maintenance and reconstruction when the wood began to rot.

As for Ginder Creek, it played an important part in the long drive to clean up Black Diamond’s sewage problem. In 1973, the annual fishing derby was forced to shut down. This popular event was held for the town’s youth on the opening day of fishing season at the Mine Pond located adjacent to Roberts Drive. According to a Seattle Times story on June 10, 1973, the State Department of Game called off the April celebration because there were no fish to catch. The cause – septic tank seepage and raw-sewer discharges. Though some of the town’s effluent was treated, other discharges weren’t disinfected before entering receiving waters.

The center of the controversy was the mobile home park on Highway 169 across from Boots Tavern. The then owner of Cedarbrook Park was Harry Blakely, who also served on the City Council. At the time, the Seattle engineering firm of Kramer, Chin & Mayo was putting together a study for “possible innovative approaches to the problem,” reported Dick Warren, vice president of the firm. By November 1978, the State Department of Ecology jumped into the fray with an eight-page memorandum detailing the sewage flows’ adverse impacts on Ginder Creek. The Ecology study found 84,000 fecal coliforms per half cup of water just twenty feet downstream from the Morgan Street culvert.

The following year, Kramer, Chin & Mayo released a recommendation to build a new sewer system with primary treatment of effluents in aerated ponds coupled with discharge into marshland lagoons. The project was financed by the EPA’s Innovative and Alternative Technology Program and was operational by early 1983. But the actual design eliminated the secondary-treatment lagoons relying instead on absorption by a vast network of wetlands plants between Jones Lake and the Roberts Drive Bridge over Rock Creek. The hoped-for “natural capture of nutrients” failed miserably, and Lake Sawyer suffered large outbreaks of algae blooms. It took years to choose a replacement design and find funding. Finger-pointing and foot-dragging followed, but by November 1992 a new $12 million system became operational and Black Diamond’s sewerage finally flowed through pipelines to King County Metro’s Renton plant.

This circa 1910 photo looking east towards Old Town comes courtesy of JoAnne Matsumura, an Issaquah historian, with photo enhancements and colorization by Boomer Burham, a Tacoma High School instructor. Research assistance was provided by Dan Dal Santo, the former City utility supervisor. A slightly different version of this photo appeared in the Black Diamond Historical Society’s 1977 calendar.