At his grave, there are few reminders of the harrowing dangers the soldier faced during the three-day Battle of Gettysburg during the Civil War. Thomas A. Davis, resting in the Black Diamond Cemetery, is memorialized with a weathered, slightly askew, gray granite headstone bearing the dimmed symbol of the Grand Army of the Republic. This veteran organization, of which Davis belonged to the Isaac Stevens Post No. 1 of Seattle, held significant meaning for him. During the latter part of his life, he joined as a connection to his past and solace for the trials he endured.

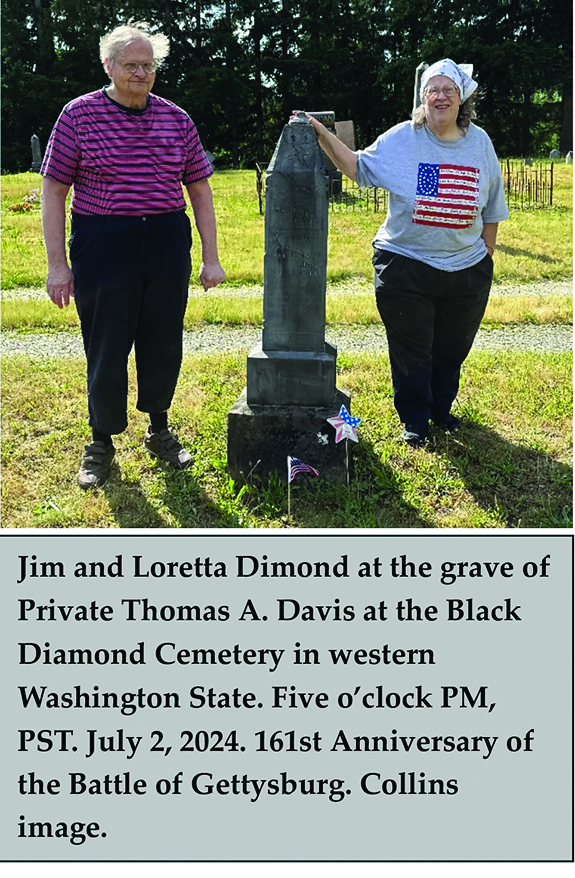

Davis is one of approximately six thousand Civil War veterans buried in Washington State and one of four at rest in the Black Diamond Cemetery. While most of their life stories have faded with time, Davis’s can be reconstructed through the tireless efforts of the husband-and-wife research team of Jim and Loretta Dimond. They have devoted themselves to tracking down every lead and gathering every snippet of information to reveal a clearer picture of the lives of America’s warriors.

According to the Dimonds, Thomas A. Davis was born in Wales in 1842 and migrated to the United States as a child. Although little is known of his early years, historical records indicate that at the outbreak of the Civil War he was already a member of Company B, 12th Pennsylvania Reserves, a local militia unit federalized as the 41st Infantry Regiment. At the time, Davis was a nineteen-year-old private. He participated in many major battles during the war, including Second Bull Run, Antietam, and the Wilderness. At least two of his brothers served as well. One suffered multiple wounds, and another, a cavalryman, was killed in action.

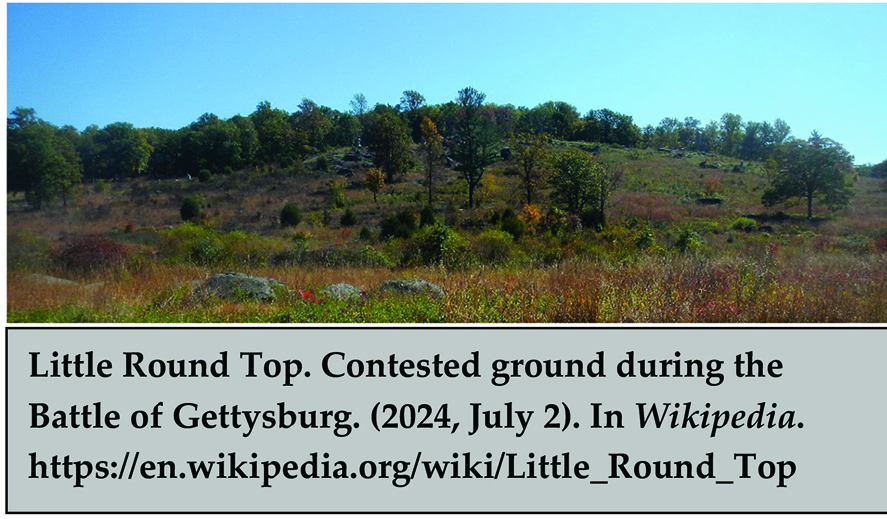

Davis’s military career peaked during the Battle of Gettysburg in the first three days of July 1863. On the second day of the famous engagement, Davis’s Company B was called to reinforce the Union’s left flank, joining Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and the 20th Maine at the conclusion of a fierce back-and-forth fight against the Confederates for the high ground at Little Round Top.

As the 12th Pennsylvania advanced over the hill, the sun cast long shadows over the Valley of Death below. Encountering light enemy resistance, Davis and his fellow soldiers quickly entrenched among the rocks. As darkness gradually enveloped the battlefield, they descended to the gap between Little Round Top and Big Round Top. It was there that they encountered several hundred exhausted Confederate soldiers who surrendered to the Union forces.

Reflecting on the significance of their actions, a member of the 12th Pennsylvania eloquently summarized their unit’s crucial role in the conflict. He emphasized that their timely arrival and bold advance had decisively turned the tide of success on the left flank, ultimately thwarting the enemy’s determined efforts on that front. The Union line had held and prevented the Confederate soldiers from capturing Little Round Top, thus preserving the Union’s position on the ridge. In the assessment of Jim and Loretta Dimond, Private Davis and Company B helped secure a triumphant victory on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, cementing their place in military history.

After taking his honorable discharge from the service in June 1864 at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Thomas Davis married and headed westward for the coalmining frontier. In about 1880, Davis relocated from Duryea, Pennsylvania (near Wilkes-Barre) to California. He settled in Black Diamond in 1883 when the Black Diamond Coal Mining Company shifted its base of operations from Nortonville in the Golden State to Washington State.

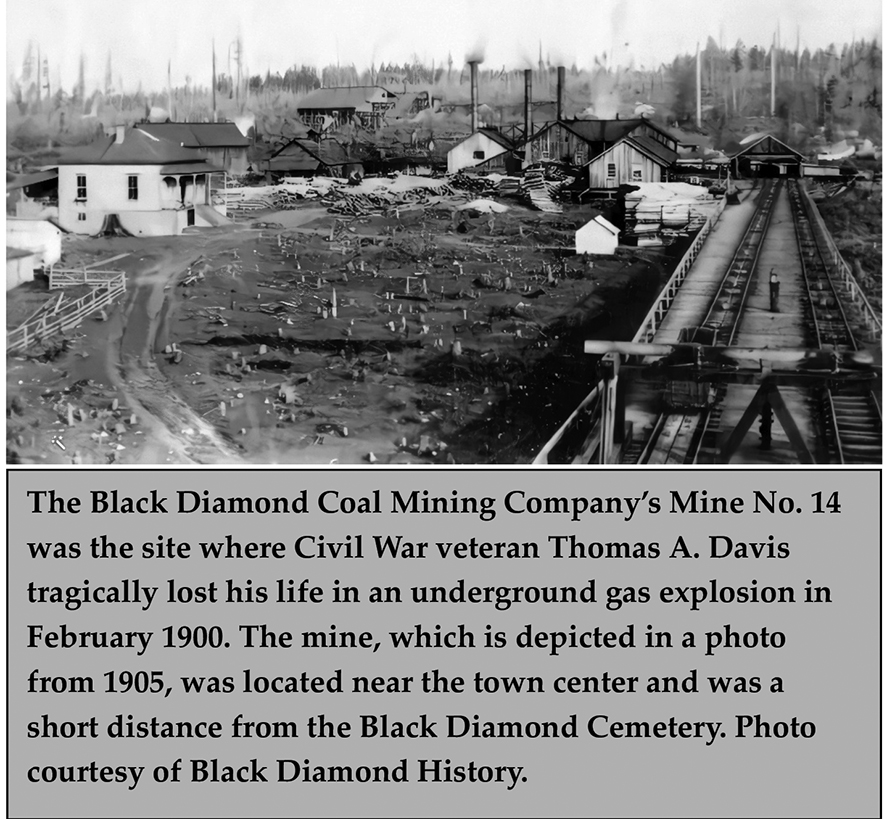

In Black Diamond, tragedy struck. Davis, a seasoned coal miner since his youth, and known as the oldest and one of the most careful on the Pacific Coast, was working in Mine No. 14, the first to open in Black Diamond.

At midmorning on February 21, 1900, he and two other miners got caught in a crushing gas explosion, entombing Davis in a subterranean coal gas pocket under tons of rock 1,500 feet below the surface. The 150-man workforce dug feverishly day and night for nearly a week to recover his body.

A coroner’s inquest unraveled much of what had happened. Death had come instantaneously. Davis was found where he fell, his head at rest on his arm and peering downward, his face suffering ghastly burns and disfigurement. Although Davis had a heavy beard, not a whisker remained.

The press reported that the entire community was mourning his death. Interment followed in the Black Diamond Cemetery, just a short distance from where he perished.

On the late afternoon of July 2 this year, Jim and Loretta Dimond placed a small American flag at Davis’s grave. They carefully coordinated their visit to coincide with the timeline of that iconic day 161 years ago when Private Davis and Company B rushed up the flank of Little Round Top. The Dimonds brought a copy of President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which they read aloud in honor of the occasion. As the sun gently sank below the tall firs surrounding the field of honor, they passionately explained that warriors such as Private Davis are heroes who must never be forgotten. And they never will be as long as Americans such as the Dimonds are dedicated to offering a glimpse into the past and paying homage to the legacy of the fallen.