As the summer concert season heats up, venues like the White River Amphitheater, Chateau St. Michelle, Marymoor Park, and the George Amphitheater will be busy showcasing pop, rock, jazz, and hip-hop acts in outdoor music venues. Washington’s weather is perfect for summer and early fall shows, but during the long rainy season, music performances turn indoors.

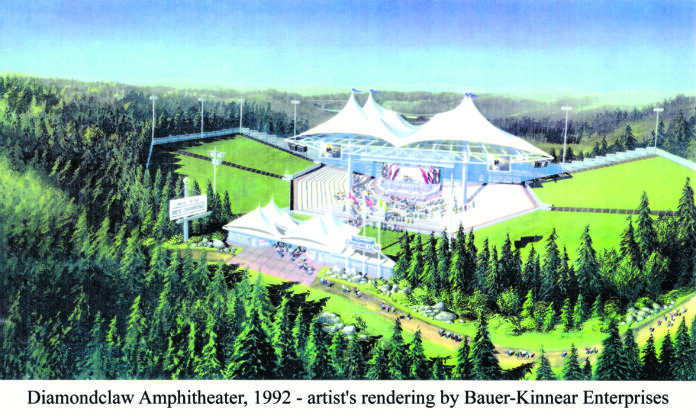

In early 1992, a site along the Green River Gorge, halfway between Black Diamond and Enumclaw was proposed for a new outdoor concert arena. Initially, it was called Diamond Claw on the Green, with the name soon shortened to Diamondclaw, combining parts of the two town’s names. The amphitheater was to occupy 12 acres of a 116-acre parcel owned by Palmer Coking Coal Co., under a 20-year lease signed in Sept. 1991. Plans called for 7,000 seats with capacity for another 11,000 patrons on a sloping grassy bowl. It would also feature hiking trails, picnic areas, and 60 acres designated for parking. The project came with a $10 million price tag.

If approved, Diamondclaw Amphitheater would have been the first outdoor concert arena built within the Puget Sound urban corridor. As reported in a July 26, 1991 Seattle Times article, the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe was also considering a 20,000-seat outdoor venue on tribal land near Auburn. At the time, there were only 47 amphitheaters in the United States, but that number grew rapidly over the years. If completed in 1994, Diamondclaw hoped to host 15 to 20 jazz festivals and rock concerts during their first year.

Diamondclaw was underwritten by Bauer-Kinnear Enterprises, a Seattle-based rock promotion company, owned by Ken Kinnear and John Bauer, with Mike Gebauer as vice president of operations. Their operating company was Arena Services Corporation, based in Renton. Over the previous seven years, Bauer-Kinnear presented more than 900 concerts in 59 venues across the Pacific Northwest. Their prior firm, Media One produced musical events at the 1986 World Exposition held in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Before teaming up with Bauer, Ken Kinnear led Albatross Productions of Seattle, promoting more than 200 concerts a year throughout the Western U.S. and Canada. He also operated Seattle’s Moore Theater from 1971 to 1973, staging various theatrical and musical productions. Later Kinnear managed the local rock group, Heart, and Firefall.

His partner headed the John Bauer Concert Company in Seattle from 1975 to 1984, which presented more than 200 concerts per year with an average annual attendance of 1.2 million fans. Most of those performances were held in the Kingdome, Tacoma Dome, Seattle Coliseum, and smaller venues in and around the Pacific Northwest. Mike Gebauer was president of U.S. Arenas which administered facilities like the Tacoma Dome and contracted programs for prestigious touring events like the 1987 U.S. Figure Skating Championship.

Within days of its announcement, Diamondclaw attracted foes, mostly residents who lived nearby. Ernie Romedo, a 76-year-old hay farmer asked, “Is this a hippie deal” and quickly answered, “If so, there’s gonna be trouble.” There were also supporters, including the Enumclaw Courier-Herald whose May 11th editorial was headlined, “Diamondclaw has the ring of fun,” arguing it would allow local fans to avoid long drives to the Gorge at George. Yet, traffic remained the major concern with the venue, as many questioned whether the two-lane Highway 169 could handle the number of vehicles needed to ferry 18,000 fans in and out of the area.

Late in May 1992, Jim Ferrato, of the newly formed group Concerned Upper Green River Citizens, planned several protests and promised to dot roads with signs opposing the amphitheater. Many who addressed an informational meeting hosted by the Enumclaw Chamber of Commerce spoke of violence, drugs, attacks from strangers, and fears for their families. Elizabeth Willis, Lee Finfer, Mike Johnson, and Patricia & Dave Stihl all wrote letters to the Courier-Herald opposing Diamondclaw. Bauer, Kinnear, and Gebauer countered their opponents’ claims with testimonials of how well the George Amphitheater was operated during their six years of management.

Studies were prepared as part of King County’s environmental review of Arena Service’s application for a conditional use permit for the concert site. However, within a year, the future of Diamondclaw grew murky. King County officials stated that no building permits had been filed. Then news leaked of Kinnear being embroiled in lawsuits with Ticketmaster Northwest, plus commercial claims, and collection efforts.

By July 1993, Bauer-Kinnear Enterprises was labeled, “financially strapped” by an in-depth article in the Puget Sound Business Journal that reported the company owed $162,555 in back taxes to the state of Washington. John Bauer of Issaquah filed for personal bankruptcy under Chapter 11. MCA Concerts, Inc. of Los Angeles explored taking over the Diamondclaw project, but negotiations stalled. In November 1993, Arena Services sold its Gorge Amphitheater to MCA for $3.9 million.

Diamondclaw came on like a heavy-metal band but exited the stage like a whispered folk song. But, 10 years later on June 14, 2003, the hometown band Heart was the opening act at the recently completed White River Amphitheater. The complex seats 16,000, with 9,000 undercover and 7,000 patrons spread along sloping lawns. White River Amphitheater covers 98 acres and is located 6.5 miles southwest of Diamondclaw.

So, why did the White River Amphitheater succeed while Diamondclaw failed? Most likely it possessed one critical asset that Diamondclaw lacked – the White River complex is situated on Reservation lands of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, the lead agency that weighed the proposal’s impacts on the surrounding environment.

This 1992 artist’s rendering by Bauer-Kinnear Enterprises comes courtesy of Palmer Coking Coal Company, a Black Diamond-based resource company founded in 1933. Next week’s column details the Aug. 1991 Lollapalooza concert at the King County Fairgrounds that might have poisoned the waters for Diamondclaw.