For generations, school children were taught, “at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month – we will remember them.” On that day and time in 1918, the Great War came to an end. It wouldn’t be known as World War I for another twenty years, when an even greater war eclipsed it.

November 11th was first commemorated as Armistice Day, later known as Remembrance Day, and in the United States, now celebrated as Veterans’ Day. It marks the anniversary of the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front after more than four years of battles on the European continent. Many European countries celebrate November 11th as Armistice Day, but throughout the British Commonwealth, it’s called Remembrance Day. Armistice Day was approved as a legal holiday by Congress in 1938, and in 1954, an amendment to the law changed the name to Veterans Day.

The first Armistice Day celebration was held in 1919 at Buckingham Palace. It included a two-minute silence as a mark of respect for the estimated 9 to 11 million military personnel who gave their lives. Millions of others died as a result of disease, accidents, and famine. In Britain, about 2% of the country’s population perished. In France, it was 4.4%, in Romania, approximately 8%, and in Serbia, an astounding 17% to 27% were estimated to have died. Mournful songs and poems memorialized the fallen, perhaps none more famous than “In Flanders Fields,” written by John McCrae, a Canadian soldier, who succumbed to pneumonia eleven months before the war’s end.

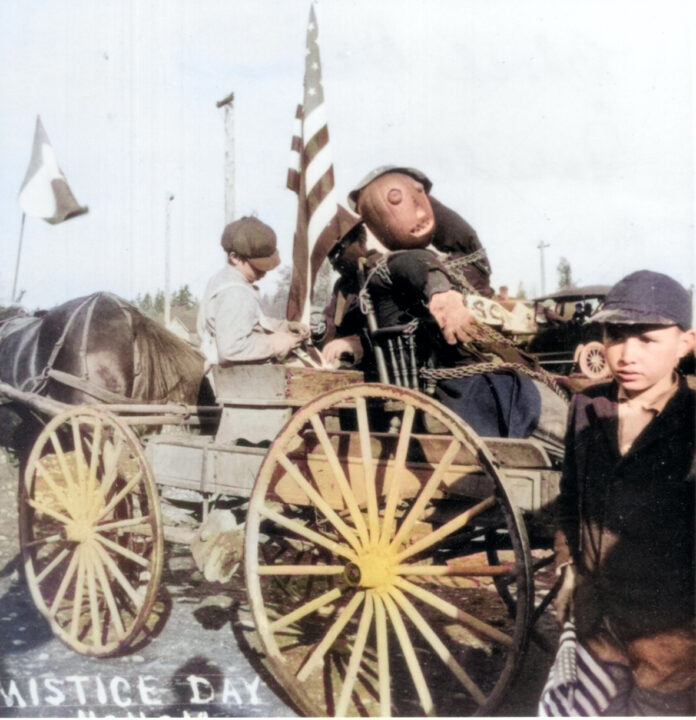

This Armistice Day photo from the Vernarelli family collection, along with the story below about Belgian families who emigrated, comes courtesy of JoAnne Matsumura, a historian and former archivist for the Black Diamond Historical Museum. Colorized enhancements were undertaken by Boomer Burnham, a Tahoma High School photography instructor who operates commercially as Boomers Photography. The photo was likely taken in the early 1920s during a parade honoring Black Diamond’s contribution to the war effort. The pumpkin to the right of the American flag was no doubt left over from Halloween. The boys in the photo may have been part of the Vernarelli family.

Fighting on the Western Front caused Belgium and France’s coal production to plummet. German troops destroyed coal mines in the occupied areas of France and Belgium. Belgium’s output dropped to almost nothing by 1918. Extreme labor shortages severely hobbled France’s yield, as miners were called up for military service. The scarcity of coal led to higher international prices. Washington State set an all-time coal production record in 1918 of 4.1 million tons, 17% higher than in 1914.

Lloyd George, then British Prime Minister, exclaimed: “Coal is the most important element in the industrial life of this country. The blood which courses through the veins of industry in our country is made of distilled coal.” Lloyd George knew coal’s importance. Welsh parents raised him, and Welsh, not English, was his first language. Wales was the United Kingdom’s primary coal-producing region.

Even before the first anniversary of Armistice Day, Black Diamond welcomed refugees from Belgium. In late July 1919, the families of Mr. & Mrs. Arthur Beaumet and Mr. & Mrs. Arthur Nicaisse, together with the latter couple’s two sons, relocated to Black Diamond. Nicaisse was Arthur Beaumet’s son-in-law. During the war, Beaumet’s home in Charleroi, one of Belgium’s largest cities, was captured by German troops. The Beaumets lost their home and property in the war, so when the fighting ceased, they resolved to begin life anew in America.