Military Air Disaster Remembered on Sixtieth Anniversary Commemorative Memorial Ceremony Conducted at Tahoma National Cemetery

By Cary Collins

It was early in a hot summer during the height of the Cold War. Nine-year-old Greg Barrowman was home in the late afternoon in Renton watching his favorite show: J. P. Patches. In the kitchen, he could hear his parents quarreling over dinner. KIRO-TV, the local network affiliate, suddenly interrupted the regularly scheduled broadcast with breaking news. A military chartered aircraft—officially Flight 293—had gone missing en route from McChord Air Force Base in western Washington State to Elmendorf Air Force Base in Alaska. The alert instantly caught Greg’s attention. That morning, he had been with his dad and mom when they had dropped off his oldest brother, seventeen-year-old Army Private Bruce Richard Barrowman, at McChord. After they said their goodbyes, Greg’s lasting image was his brother turning away with his black duffle bag swung over his shoulder and walking towards the aircraft with the other travelers.

Private Barrowman had been on a home visit from Fort Ord, an Army post in Monterrey, California, where he had completed a course in Business Administration. Having enlisted in January after dropping out of Renton High School, Private Barrowman had been assigned to Fort Richardson, an Army installation in Anchorage. Now, the identities of the 101 passengers on board the flight taking him there flashed alphabetically on the television screen. Greg watched the scroll three times to ensure he saw it correctly. He had. His brother—who he describes as athletic, intelligent, sensitive, kind, sober and compassionate—was among the missing. Greg walked into the kitchen to tell his parents. At first, they brushed him off but went into the living room to check when their son insisted.

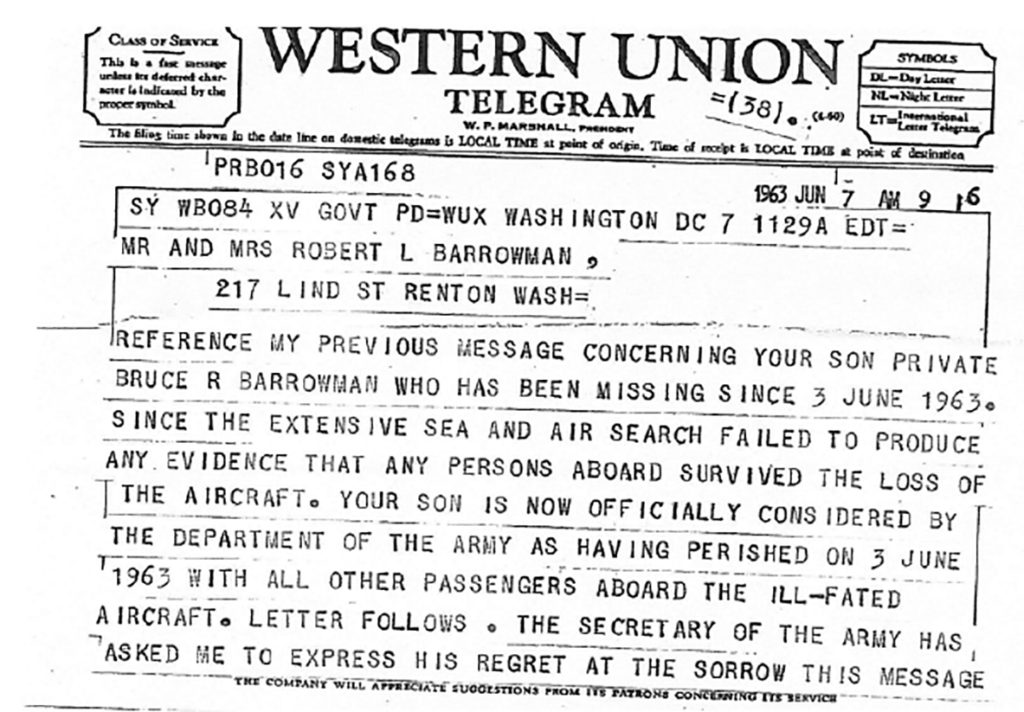

Stiffening, they felt the agony that grips all parents when their child is in danger and can’t be reached. That “anxiety and uncertainty” swept over Robert Barrowman and his wife, Barbara, on that fateful third day of June 1963. The news, Greg says, put the whole family on hold, a situation exacerbated later that day when he broke his ankle playing on a Tarzan swing. The Barrowman’s worst fears would be realized as the days of horrors passed. The aircraft had plummeted into the Gulf of Alaska. There were no survivors. Their son was dead. Greg Barrowman stood beside his mother when the Department of the Army made it official. Two uniformed soldiers knocked on the front door of their house with a Western Union telegram in hand that communicated the final determination of his status.

The mood was somber and reflective. About seven weeks had passed since the military chartered four-engine DC-7C had gone down. Some wreckage and belongings of the passengers on board had been recovered, but no human remains. Private Barrowman’s parents and siblings—Robert Barrowman came up with the idea, and neighbors helped pour the concrete base—had erected a thirty-foot flagpole in front of their Renton home to honor their son and brother. Assigned as a member of the Honor Detail tasked with dedicating the flagpole was twenty-five-year-old Private First Class Bernard “Bernie” Moskowitz, an Army assistant armorer stationed at Fort Lawton in Seattle. Knowing how to bugle, PFC Moskowitz had occasionally sounded Taps at military services, having done so the week before at a funeral conducted at the Fort Lawton post cemetery. On July 22, 1963, he performed the same service for another fallen soldier. Today, Bernie recalls his participation in that flagpole dedication and memorial service for Private Bruce Barrowman:

I was a member of Headquarters Platoon, Headquarters Company, Sixth Army, United States Army Garrison, Fort Lawton, Washington. I had been sounding Taps from time to time at Fort Lawton.

One day, I was called into the Day Room at Fort Lawton for a briefing by 1SG Woodward L. “Woody” Jenkins. I was familiar with other soldiers there as members of the Falcon Rifle Squad of Fort Lawton. Others I didn’t know.

1SG Jenkins informed us that we would perform the dedicatory service in Renton on July 22 and told us why. This was the first I had heard about the crash and the loss of life, or at least that I can remember. There might have been something on the news or in the newspaper, but I don’t recall seeing anything specific and had no idea what had happened. Now I would be involved.

I was to be in proper dress: an all-cotton khaki shirt and pants, a service cap with visor, white gloves, low quarters (regular street shoes) and not boots, and a white pistol belt (but I didn’t have one, so I wore a black belt). The dedication team would include the bugler, six shooters, two sergeants, two to four Military Police (who may have come in their own vehicle), and the commander. We were instructed to report back to the Day Room in one week at 9 AM.

Parenthetically, I explained to the 1SG that I lived in Renton and asked, “Couldn’t I just drive to the family home in Renton and meet everyone there and drive back to my home after the dedication?” He responded in a very 1SG manner: “I want you all here at 9 AM to get on the bus.”

We assembled at Fort Lawton on Monday morning, June 22, as directed. We then drove to the Barrowman home in Renton, in an older but nice neighborhood, maybe a half-mile from Renton High School, where Bruce Barrowman, the fallen soldier we would be honoring, had gone to school.

It was quiet when we arrived, and the mood became solemn as we grouped or formed up and assumed our places. The parents, their four surviving children, relatives, and neighbors were there. There might have been fifteen in all. The father, a Second World War Army veteran, was not what I would call resolute but trying to hold it together. The mother was stoic. Over a month had passed since the crash, and you could tell they were hurting. There were newspaper people there and a cameraman and a military photographer.

We began the service to dedicate the flagpole that the Barrowmans had erected in front of their home to honor their lost son and brother. I don’t remember what was said during the ceremony. Several Army officers were there, and I am sure they said some words. I don’t recall if either of the parents spoke. We folded and presented to the parents the tri-folded American flag, fired the volleys, and I sounded Taps. The ceremony lasted about a half-hour to forty-five minutes. Pictures were taken, some of which were staged. We reboarded the bus and returned to Fort Lawton after the dedication.

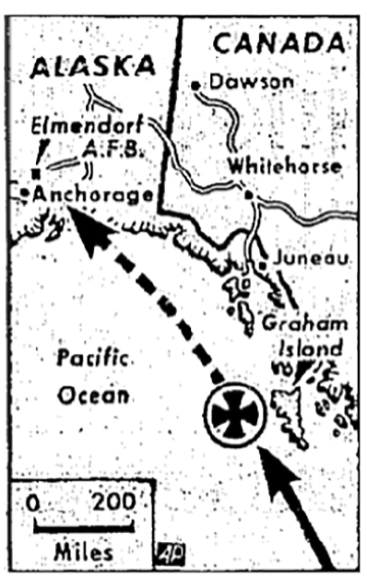

Sixty years later to the day and almost to the minute, Bernie Moskowitz sounded Taps again for Private Barrowman and the fallen of Flight 293, this time at a Commemorative Memorial Ceremony conducted at Tahoma National Cemetery in Maple Valley, Washington. At the June 3, 2023, honoring event, which included a military flyover and the dedication of a memorial in the Memorial Walk-way, family members traveled from across the United States to remember and recognize the lives lost. Greg Barrowman served as organizer and master of ceremonies. He and other speakers recalled their loved ones and the circumstances of the crash. The pilot and crew were all from the Seattle area. Fifty-eight service members represented the Army, Air Force, and Coast Guard service branches. Seventeen were Civil Service employees. Twenty military dependents were on board, 28 women and children, and six family groups. The crash of Flight 293 was, at the time, the third costliest disaster in military lives. The airliner, chartered by the Military Air Transport Service, had left McChord Air Base at about eight o’clock in the morning and had been in the air for two hours and thirty-six minutes when last heard from at a bearing 150 miles northwest of Ketchikan, Alaska. The commitment of the survivors was evident throughout the Tahoma ceremony. For them, it is personal. They will never forget. They will continue working tirelessly to discover what happened, even to the extent of locating and recovering the airplane’s wreckage and the passengers’ remains

For Bernie Moskowitz, his participation in the two honoring ceremonies resonates deeply. He knows, more than most, the trauma and heartache of loss. As the Chief Bugler at Tahoma National Cemetery for over two decades, Bernie has sounded Taps at thousands of military funerals. He has also remained intimately in contact with the Barrowman family. Hired as the Automotive teacher at Renton High School in 1967, Bernie taught Alan Barrowman, another younger brother of Private Barrowman. Alan took small engines and power mechanics in his first year. He was then a student in Bernie’s automotive course in his second year. Alan Barrowman was killed by a drunk driver in a tragic automobile accident a few days before Christmas in 1969 when he was sixteen. To honor Alan, Bernie and his shop students had a plaque made that Bernie presented to the youngest Barrowman sister, Nancy, at her graduation from Renton High School. She still has it today. “Alan was just a sweet guy, and his death bothered all of us, and we wanted to do something,” Bernie recalls as the inspiration for the act of kindness and caring.

To lose two teenage sons was almost more than the Barrowman parents could bear. As Greg puts it, his dad and mom were “left in body casts for the remainder of their lives.” It has been a consuming struggle for all Flight 293 families, each suffering, in their own way, including those children who, opposite the Barrowmans with the death of their boys, grew up without a father or mother. But as the ceremony at Tahoma National Cemetery and Bernie’s support spanning six decades attests, they share an uncommon bond. They hold close and are there for each other. They always will be.